Table of Contents

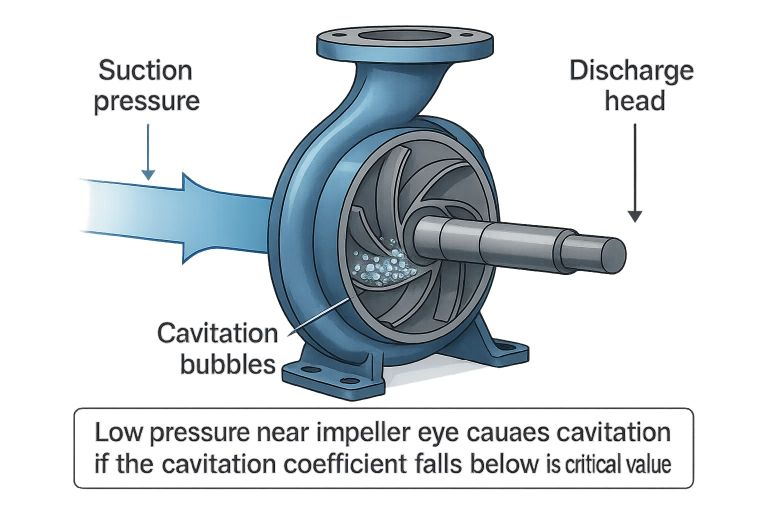

Cavitation coefficient is used to define if the pump would cavitate. Cavitation is one of the most critical issues in centrifugal pump design and operation. When the static pressure at the impeller eye drops below the liquid’s vapor pressure, vapor bubbles form and collapse violently as they move into higher-pressure regions. The result is metal erosion, noise, vibration, and a reduction in efficiency.

To quantify how close a pump operates to the onset of cavitation, engineers use a dimensionless parameter known as the cavitation coefficient.

Concept and Definition

The cavitation coefficient expresses the ratio between the available suction head margin (the energy available to prevent vaporization) and the total head developed by the pump. It allows comparison between pumps of different sizes and speeds and provides a convenient way to determine safe suction conditions.

The most common form is:

\[σ\ =\ \frac{NPSH_{availabe}}{H}\]

Where;

σ = cavitation coefficient (dimensionless)

NPSHavailable = net positive suction head available (m)

H = total head developed by the pump (m)

This form known as the Thoma coefficient—was first described in early turbine studies and adopted later for centrifugal pumps. It provides a direct link between available suction head and the head developed by the machine.

Alternative Energy-Head Formulation

When suction pressure, velocity, and friction losses are known, the same concept can be written explicitly as:

\[C\ =\ \frac{\left(\frac{ΔP}{𝜌g}\ +\ \frac{u^2}{2g}\ -\ h\right)}{H}\]

Where

ΔP = difference between suction absolute pressure and vapor pressure (Pa)

ρ = liquid density (kg/m³)

g = gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s²)

u = flow velocity at suction inlet (m/s)

h = head loss in suction line (m)

H = pump total head (m)

The numerator represents the effective head available above vapor pressure at the impeller eye. The denominator normalizes this available head to the pump’s total developed head.

Both forms are equivalent; they simply use different measurable quantities.

Comparison of the Two Forms

| Aspect | Energy-Head Form (C) | Thoma Form (σ) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression | C = [ (dP/p.g) + (u2/2.g) – h ] / H | σ =NPSHavailable/H | Both represent the ratio of suction margin to total head. |

| Numerator meaning | Explicit suction head above vapor pressure, considering velocity and losses | Equivalent suction margin expressed as NPSH | Physically identical quantities written differently. |

| Denominator | Total pump head | Total pump head | Used for normalization. |

| Symbol | C | σ | Different notation; same concept. |

| Units | Dimensionless | Dimensionless | Ratios of heads. |

| Interpretation | High ( C ) → safe operation; Low ( C ) → cavitation likely | High (σ) → safe operation; Low (σ) → cavitation likely | Identical physical meaning. |

| Use | Helpful when pressure, velocity, and friction losses are directly known. | Often found in pump and turbine design charts provided by manufacturers. | Either option can be used to evaluate cavitation margin based on the available data.. |

Worked Examples

Example 1: Using the Thoma Form (σ)

A pump develops a total head H = 25m

The available NPSH at the installation is measured as NPSHavailable=4.5m

\[σ\ =\ \frac{4.5}{25}=\ 0.18\]

If the manufacturer’s test data shows that cavitation begins at a critical value σcrit=0.12 then:

σavaialable > σcrit

✅ The pump operates safely, because the available cavitation coefficient (0.18) exceeds the critical value.

Now imagine the same pump operates with slightly warmer water, reducing NPSHavailable to 3 m:

\[σ\ =\ \frac{3}{25}=\ 0.12\]

Here the value just equals the critical limit – incipient cavitation may occur at the impeller eye.

This example demonstrates how sensitive the cavitation coefficient is to suction conditions.

Example 2: Using the Energy-Head Form (C)

Suppose a centrifugal pump draws water (ρ = 998 kg/m³) from a tank.

At the suction flange, a pressure gauge reads 55 kPa abs, the water temperature is such that vapor pressure = 2 kPa, the suction velocity u = 2.5m/s, and frictional head loss in the suction pipe h = 0.6m

The total head developed by the pump is H =18m

1. Convert pressure difference to head:

\[\frac{ΔP}{𝜌g}=\ \frac{55000−2000}{998\ \cdot\ 9.81}\ =\ 5.42\ m\]

2. Velocity head:

\[\frac{u^2}{2g}\ =\ \frac{2.5^2}{2\cdot9.81}\ =\ 0.32\ m\]

3. Combine terms:

Effective suction head = 5.42 + 0.32 − 0.6 = 5.14m

4. Compute cavitation coefficient:

\[C\ =\ \frac{5.14}{18}=\ 0.29\]

If the manufacturer indicates that cavitation begins at Ccrit = 25

Then = 0.29 > 0.25 → Safe operation.

Should the suction pressure drop to 45 kPa abs, repeat the same steps:

\[\frac{ΔP}{𝜌g}=\ \frac{45000−2000}{998\ \cdot\ 9.81}\ =\ 4.38\ m\]

Then

\[C\ =\ \frac{4.38\ +\ 0.32\ -\ 0.6}{18}\ =\ 0.23\ <\ 0.25\]

Now the pump would likely cavitate, confirming how reduced suction pressure lowers the cavitation coefficient.

Relation to Pump Specific Speed

Experimental data summarized by Stepanoff (1957) and Gülich (2008) show that the critical cavitation coefficient decreases with increasing specific speed.

Approximate ranges:

| Pump Type | Specific Speed (metric) | σ₍crit₎ range |

|---|

| Radial-flow | 20–60 | 0.3–0.5 |

| Mixed-flow | 60–150 | 0.15–0.3 |

| Axial-flow | 150–300 | 0.05–0.15 |

This trend explains why axial pumps can tolerate lower suction heads compared with radial pumps

Influence of Fluid Density

Since the pressure head term involves 1/𝜌, increasing the liquid density decreases the head equivalent for the same pressure difference. A 3% rise in density therefore reduces the cavitation coefficient by roughly 3% if all other conditions are constant.

For water, this effect is minor, but for heavy hydrocarbons or cryogenic fluids the correction may become important.

Practical Interpretation

In design practice:

- Increase C or σ by raising suction pressure, lowering liquid temperature, or reducing line losses.

- Avoid sharp bends or throttling valves on the suction side.

- Verify σ > σ₍crit₎ for the entire operating range, not only at best efficiency point.

Maintaining a sufficiently high cavitation coefficient ensures quiet, efficient operation and long service life of the impeller and bearings.

Summary

The cavitation coefficient is a fundamental measure linking the suction energy available to the total head produced by a centrifugal pump.

Whether expressed as:

\[σ\ =\ \frac{NPSH_{availabe}}{H}\ \]

OR

\[C\ =\ \frac{\left(\frac{ΔP}{𝜌g}\ +\ \frac{u^2}{2g}\ -\ h\right)}{H}\]

it quantifies the margin separating normal operation from cavitation.

Both theoretical reasoning and experimental data confirm that keeping this coefficient above its critical value is essential to prevent bubble formation and damage.

Through the examples shown, it is clear that the two formulations differ only in how the suction head is evaluated. Understanding and monitoring the cavitation coefficient helps engineers design more reliable, efficient, and durable pumping systems.

External useful links

Cavitation coefficient calculator – Android application

Process Engineering Calculator – Windows Software